CAÏRO - This year, Egypt is hosting the international climate summit COP27. An African first of symbolic importance, but international organisations like Amnesty International point to the serious abuses in Egyptian prisons. They see the Egyptian presidency as an attempt to polish the regime's image before the international community.

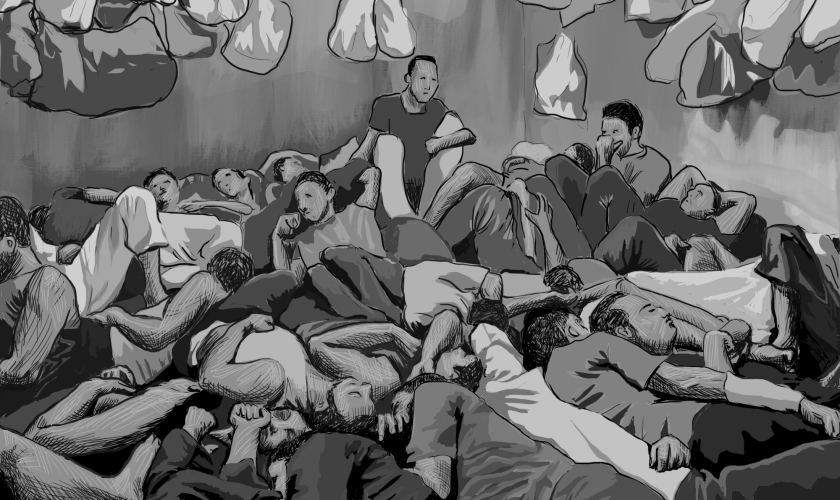

Since General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi seized power in 2014, the number of political prisoners in Egypt has risen to some 60,000. Al-Sisi's waves of arrests have turned Egypt into a land of families torn apart. The conditions in the cells are degrading. The arrests are also a curse for the families involved. They pay sky-high sums to visit their relatives in prison and provide them with medicine and other basic needs. It is often unclear how long a loved one will remain in prison. The prisoner's right to communication with the outside world has also been under pressure for years.

Yet many affected families are fighting back. They are uniting on social media to provide for inmates' necessities and to smuggle letters past prison gates. Their call for justice transcends national borders. The Egyptian diaspora and human rights organisations are joining forces around the world, including in Belgium, to demand the release of political prisoners. But international diplomats often turn a blind eye to Egypt's human rights record, in exchange for strict border policies and lucrative trade contracts.

Disclaimer by the author

This article deals with a very sensitive subject. It shows courage that the people featured in the article are willing to speak out about it. Many of them no longer live in Egypt and have no intention of returning as long as President al-Sisi is in power. Those who do still live in the country and have testified, such as members of the Seif family, Eida Seif al-Dawla and Mohamed Lotfi, seem to have accepted their fate as members of the persecuted opposition. Incarceration hangs over their heads like a sword of Damocles. All they can hope for is that their network will deter the regime, for fear of an international scandal.

My Belgian passport offers me privileged protection. Yet publishing my name would probably lead to my exile from Egypt, a country and society I have come to love. Therefore, I have decided to remain anonymous. However, I am prepared at any time to be held accountable for this research through the editors of MO*.

Illustration: ©Shalabeyya

ONLINE

- Aan de andere kant van de tralies: de gebroken families van al-Sisi's Egypte, MO.be, 04/11/2022.

- On the other side of the bars: the broken families of el-Sisi's Egypt, MO.be, 04/11/2022.

- De l'autre côté des barreaux: les familles brisées de l'Égypte d'Al-Sisi, MO.be, 04/11/2022.

- الجانب الآخر من القضبان - العائلات المُحطَّمة في مصر-السيسي, MO.be, 04/11/2022.

- Al otro lado de los barrotes: las familias rotas del Egipto de al-Sisi, MO.be, 04/11/2022.